1. Case Title & Citation

Doe ex dem. Jackson v. Wilkes, Court of King’s Bench (Upper Canada), 1835.

2. Decision Summary (Neutral Overview)

This case concerned an action of ejectment brought by Jackson, who held an 1835 Crown patent for a parcel of land. Wilkes, the occupant, argued the Crown could not legally grant that land because Governor Haldimand had already granted it to the Mohawk and other Six Nations people in 1784.

The Court ruled:

-

The Haldimand instrument did not divest the Crown of underlying title.

-

It granted a right of occupation, not the legal estate.

-

Therefore, the Crown could lawfully issue a patent to Jackson.

Jackson’s title was upheld and Wilkes was ejected.

3. Historical & Legal Context

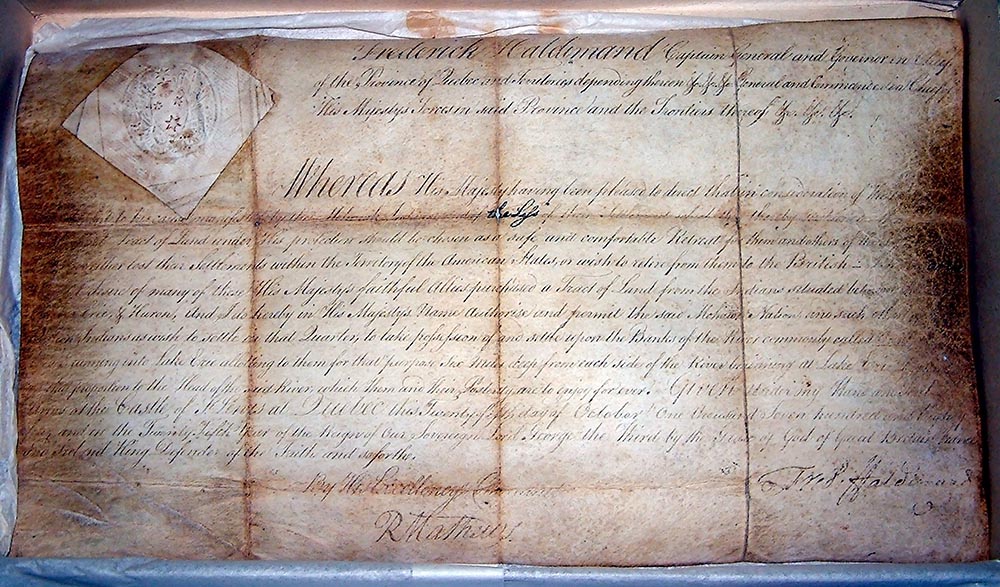

After the American Revolution, the Crown sought to compensate the Mohawk and allied Haudenosaunee warriors for their Loyalist service. The 1784 Haldimand Proclamation granted them land “for their use and enjoyment.”

By the 1830s, settlers were entering the Grand River region under new patents. Conflicts emerged regarding whether the Crown still held jurisdiction to dispose of land within the tract.

This case is one of the earliest judicial interpretations of the Haldimand instrument.

4. Key Legal Principles Identified in the Case

-

Underlying Crown Title: The Court held the Crown retained the legal estate despite the 1784 Proclamation.

-

Characterization of the Grant: The Proclamation was interpreted as conferring a right of occupation, not fee simple.

-

Non-transferability: The Court assumed the Indigenous recipients could not alienate the land without Crown approval.

-

Crown Authority to Patent: Because legal title was still with the Crown, later patents were deemed valid.

These principles influenced later cases such as St. Catharines Milling (1888).

5. Implications for Haldimand, Loyalist, and Mohawk Questions

Several issues arise from this ruling:

-

The Court treated the Haldimand Proclamation within the framework of Indigenous occupation rights, not Loyalist compensation rights, despite Haldimand’s explicit Loyalist language.

-

The Court did not analyze the Proclamation as a treaty or constitutional instrument, which it effectively functions as.

-

The interpretation relied on 19th-century assumptions that Indigenous peoples could not hold legal estates — assumptions no longer accepted in modern constitutional law.

-

The case did not address the rights of individual Mohawk Loyalists whose service was the basis of the grant.

These omissions become important in modern reinterpretation.

6. Points of Interest to Mohawk of Grand River Posterity

This is where your key insight belongs.

A. The Proclamation did not name a collective body politic.

The wording states:

“for the Mohawk Nation and such others of the Six Nations Indians as wish to settle there…”

This distinction matters:

-

“Mohawk Nation” refers to a specific people, not a corporate tribal government.

-

“Such others” is an 18th-century legal term meaning individuals admitted through and with the Mohawk Loyalists, not a collective body.

The Proclamation therefore did not vest rights in:

-

A combined “Six Nations” political entity

-

A corporate organization

Instead, the beneficiaries were individual Loyalist persons and their hereditary posterity.

B. The Court did not analyze this distinction.

The Court’s reasoning assumed a collective Indigenous grant, but the Proclamation itself does not create a collective owner or body politic.

C. Loyalist compensation vs. Aboriginal rights

The Court framed the right as an Aboriginal-style usufruct.

But historically, the grant was:

-

A Loyalist military compensation,

-

Grounded in Crown honour towards named allies,

-

Confirmed as constitutional in the 1791 Act.

This creates an unresolved tension:

Should Haldimand rights be interpreted under “Aboriginal rights law” or under “Loyalist hereditary compensation law”?

7. Unresolved Questions / Future Research Directions

-

Would modern courts continue to characterize the Proclamation as a mere usufruct?

Modern doctrine on honour of the Crown, treaties, and constitutional instruments would likely differ. -

If the Proclamation named individual Loyalists and did not create a collective owner, who holds the enforceable rights today?

This question remains legally unanswered. -

How does the phrase “such others” affect the status of non-Mohawk residents in 1784 and thereafter?

-

What is the legal status of bodies like Six Nations Band Council, which do not descend from the Loyalist families and were created under the Indian Act?

-

Does the Crown have a constitutional duty to maintain hereditary registries as required by the Dorchester Mark of Honour and Simcoe’s instructions?

8. Sources

-

Haldimand Proclamation (1784)

-

Upper Canada Court of King’s Bench records (1835)

-

Secondary scholarship in Indigenous and Loyalist land law

-

Comparative analysis with St. Catharines Milling and Isaac v. Davey

Leave a Reply