-

Case Title & Citation

Federal-Provincial Arbitrations (1897): Indian Claims / Robinson Treaties (Opinion of Curran Q.C.)

(Arbitration opinions and reports prepared for the Dominion–Ontario dispute over responsibility for Indian claims under the Robinson Treaties.) -

Decision Summary (Neutral Overview)

In the late 19th century, the Dominion of Canada and the Province of Ontario submitted several disputes to arbitration regarding:

-

Which level of government was financially responsible for Indian claims arising under the Robinson Treaties and related arrangements.

-

How to allocate the burden of annuities, increases in payments, and other treaty obligations.

As part of these arbitrations, legal opinions were prepared by counsel including Curran Q.C. These opinions examined:

-

The nature of the Crown’s obligations to Indigenous signatories.

-

Whether those obligations were properly federal, provincial, or shared.

While not a single “court judgment,” the Federal-Provincial Arbitrations and Curran’s opinion have been treated as important interpretive authorities on the constitutional and fiduciary character of treaty obligations.

-

Historical & Legal Context

After Confederation (1867), the new Dominion and provinces immediately began arguing over who should pay for what:

-

The federal government had jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians” under s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

-

The provinces held beneficial ownership of Crown lands and resources under s. 109.

Where treaties promised annuities or other benefits funded from land and resource revenues, it was not obvious whether these were a federal charge, a provincial charge, or some combination.

The 1897 arbitrations addressed these tensions and treated treaty obligations as a serious, ongoing constitutional responsibility—not a discretionary policy.

-

Key Legal Principles Identified in the Authority

From the way these arbitrations and Curran’s opinion are used, several principles stand out:

-

Treaties create real, continuing obligations that must be honoured, not symbolic gestures.

-

There is an interlocking responsibility between federal and provincial governments, especially where treaty promises are tied to land and resource revenues.

-

Treaty obligations cannot simply be wished away or treated as optional because they are inconvenient to either level of government.

-

The Crown, in both its federal and provincial manifestations, must treat Indigenous treaty claims as part of the constitutional architecture of the Dominion.

-

Implications for Haldimand, Loyalist, and Mohawk Questions

For Six Miles Deep and the Grand River:

-

The Federal-Provincial Arbitrations and Curran Q.C.’s analysis show that, even in the 1890s, Canada recognized treaty-like Indigenous obligations as constitutional business, requiring formal dispute resolution between levels of government.

-

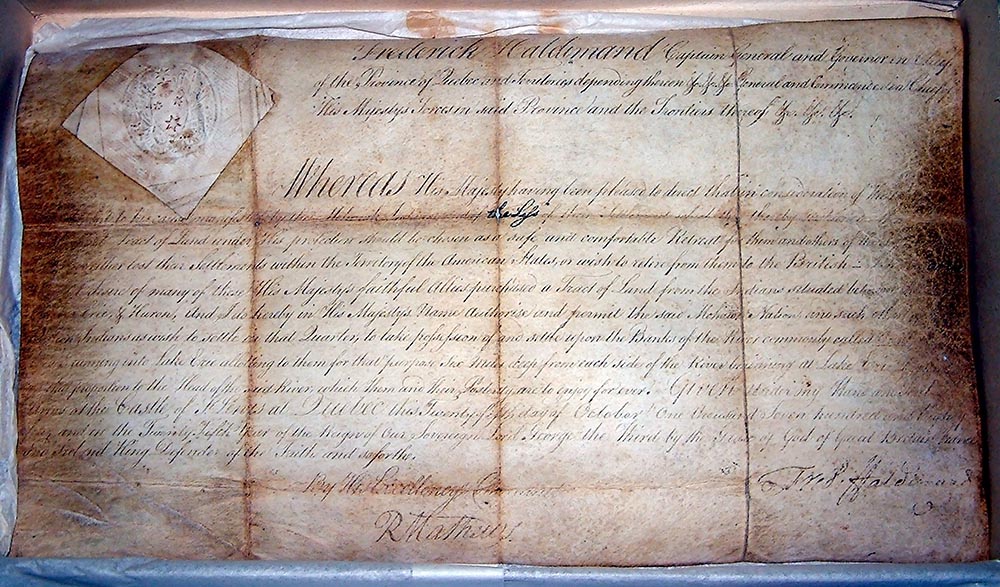

By analogy, the Haldimand Proclamation and its related instruments (Haldimand Pledge, Dorchester’s Mark of Honour, Simcoe’s Proclamation) should be treated at least as seriously as the Robinson Treaties were in 1897:

-

They involve Crown-purchased lands set apart for Indigenous and Loyalist posterity.

-

They shape who should benefit from land and resource use on the tract.

-

They raise the same kind of question: who must honour and fund the promises—Canada, Ontario, or both?

-

-

The 1897 approach undermines any modern claim that Haldimand is “purely federal” or “purely provincial” or nobody’s problem. If they could arbitrate over Robinson obligations, they can—and arguably must—face the Haldimand obligations in a similar constitutional frame.

-

Points of Interest to Mohawk of Grand River Posterity

-

Curran’s work is part of your argument that Canada once took Indigenous financial obligations seriously enough to litigate and arbitrate them between governments.

-

It reveals a double standard:

-

Robinson Treaties: formal arbitration, legal opinions, careful allocation of responsibility.

-

Haldimand Proclamation and Mohawk Loyalist posterity: largely ignored or reduced to “heritage” while land is taxed and developed.

-

-

For Mohawk Loyalist descendants on the Grand River, the Federal-Provincial Arbitrations serve as a precedent for what proper Crown behaviour looks like:

-

Acknowledging that the obligation exists,

-

Accepting that it is constitutionally serious, and

-

Working out, in law, who must pay and perform.

-

-

Unresolved Questions / Future Research Directions

-

If Canada and Ontario were willing to arbitrate over the Robinson Treaties in 1897, what would it look like to convene a modern Haldimand reference or arbitration:

-

To determine the extent of federal and provincial obligations,

-

To allocate responsibility for past breaches, and

-

To design a funding and jurisdictional framework going forward?

-

-

Could the logic of those arbitrations be used to argue that Ontario cannot simply keep the benefit of Haldimand lands and taxes while federal authorities duck their fiduciary role?

-

How might the 1897 materials support a position that Haldimand is part of Canada’s “title story”, and that ignoring it now is out of step with the Crown’s own past practices?

-

Sources

-

Federal-Provincial Arbitrations (1897), including Curran Q.C.’s opinion on Indian claims and the Robinson Treaties (as cited in your Memorandum of Law).

-

Historical scholarship on Dominion–Ontario disputes over treaty obligations and Indian claims.

Leave a Reply