1. Case Title & Citation

Logan v. Styres, [1959] O.R. (Ontario High Court of Justice).

2. Decision Summary (Neutral Overview)

Logan v. Styres addressed questions of standing, authority, and representation in matters connected to lands and governance along the Grand River. The Court declined to recognize claims rooted in traditional or hereditary authority and instead treated modern statutory and administrative bodies as the appropriate legal representatives.

The Court did not undertake a detailed examination of the eighteenth-century Crown instruments governing the Grand River. Instead, it proceeded on the assumption that claims not already recognized within contemporary statutory frameworks—particularly those created under the Indian Act—did not give rise to enforceable legal standing.

- Parties: Joseph Logan (a Mohawk Chief) and others challenged the Indian Act and a Privy Council Order (P.C. 6015) that replaced hereditary chiefs with an elected council.

- Core Issue: Whether the Canadian Parliament had the authority to impose its elected system on the Six Nations, overriding their traditional hereditary leadership.

- Court Ruling: The Ontario High Court dismissed the action, stating Parliament did have the authority to legislate for the Six Nations, including land matters, and that the Order in Council wasn’t invalid (ultra vires).

- Significance: It confirmed Six Nations people were subject to Canadian laws but also recognized their distinct system of governance, setting a precedent for future conflicts over Indigenous self-determination and the Indian Act.

- Hereditary vs. Elected: This case reflects a long-standing conflict at Six Nations between the traditional Haudenosaunee Confederacy (hereditary chiefs) and the Indian Act elected band council.

- Ongoing Legal Battles: The issues raised in Logan v. Styres continue to resonate in other legal challenges, such as the massive land claims litigation involving Six Nations and the Crown.

3. Historical Framework: Restoration, Not Aboriginal Rights

This case cannot be properly understood without returning to the Crown’s Loyalist and constitutional instruments, which form a distinct legal framework separate from modern Aboriginal rights doctrine.

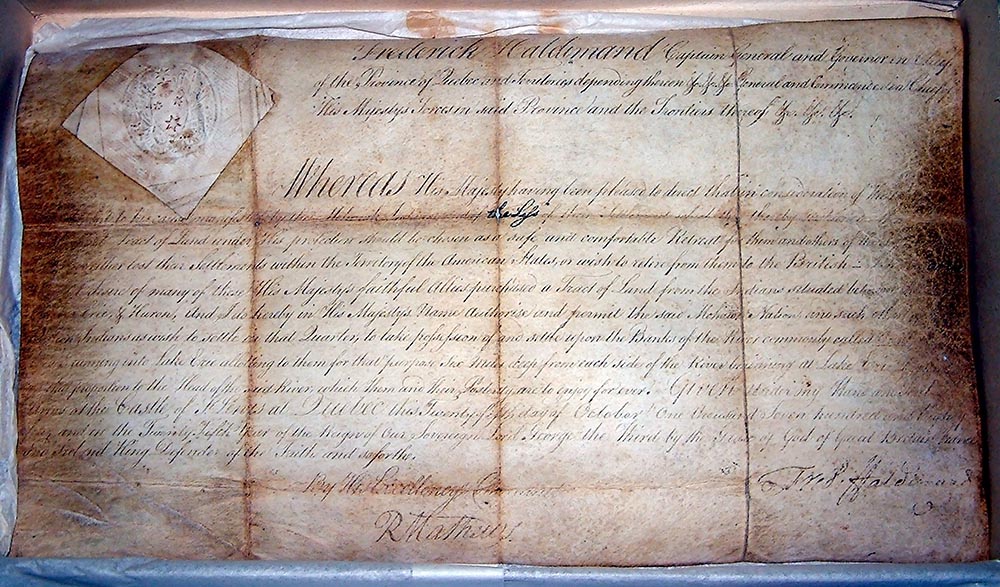

The Haldimand Pledge of 1779 was a wartime commitment made to the Mohawk and allied Haudenosaunee who had remained steadily attached to the King’s cause. It promised that, once hostilities ended, they would be restored to the same condition they occupied before the American Revolutionary War—status quo ante bellum. This was not a grant of new rights; it was a promise of restoration grounded in alliance and service.

That pledge was implemented through the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784, which authorized the Mohawk Nation and “such others of the Five (later Six) Nations Indians as wish to settle there” to take possession of lands along the Grand River “which they and their posterity are to enjoy forever.”

This framework is not an Aboriginal rights framework. It is a Loyalist compensation and restoration framework, rooted in Crown honour and military alliance.

4. Jackson v. Wilkes and the Absence of Natural Persons

In Doe ex dem. Jackson v. Wilkes (1835), the Court identified a critical structural problem in the Haldimand Proclamation: it did not name any natural persons capable of taking and transmitting a legal estate.

The Court held that:

-

The Proclamation did not create a body politic,

-

It did not incorporate a collective entity,

-

And it did not vest legal title in named individuals.

As a result, the Court characterized the Proclamation as conferring a right of occupation rather than a legal estate in fee simple.

Whether that conclusion was correct is less important here than what it revealed: the Proclamation alone did not identify who, in law, was to carry the interest forward. It named peoples, not persons.

That omission made a secondary mechanism constitutionally necessary.

5. Dorchester’s Mark of Honour and Simcoe’s Ascertainment Process

The Mark of Honour, created by Lord Dorchester in 1789, must be understood as the Crown’s response to this problem. It was not a decorative or symbolic gesture. It created a hereditary distinction for Loyalists and their descendants “by either sex” and directed that they be identified, recorded, and preserved in public records.

Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe then supplied the required procedure. His proclamations instructed Loyalists and their posterity to ascertain their status upon oath before magistrates, so that registries could be created and maintained.

Together, Dorchester and Simcoe provided what the Proclamation alone did not:

-

Identification of natural persons,

-

A lawful method of proof,

-

And a mechanism for hereditary continuity.

This framework was designed to operate without reference to Mohawk customary law and without reliance on collective Aboriginal rights. It was a Crown-designed Loyalist system for identifying individual beneficiaries.

6. The Error Repeated in Logan v. Styres

Logan v. Styres repeated the same foundational error identified in earlier cases, but in a modern administrative form.

The Court denied standing without first asking:

-

Whether the Crown had ever completed the ascertainment process it promised,

-

Whether hereditary Loyalist posterity existed and could be identified,

-

Or whether the Crown’s failure to maintain registries undermined its own position.

Standing was denied before ascertainment, rather than after it.

This is not a failure of Mohawk customary law. It is a failure to apply the Crown’s own Loyalist machinery.

7. Why This Project Rejects Collective-Rights Framing

A central feature of the Six Miles Deep approach is what it intentionally avoids.

Most Grand River litigation has been framed through:

-

Aboriginal rights doctrine, or

-

Mohawk customary governance.

Courts then respond by asking which collective governs, which council represents, and which body holds authority. That framing almost inevitably collapses claims into Indian Act structures or generalized “Six Nations” representation—regardless of what the original Crown instruments say.

This project does not ask courts to adjudicate Indigenous sovereignty or customary law.

Instead, it asks a narrower and more orthodox question: did the Crown follow its own Loyalist and constitutional instruments?

Those instruments speak of:

-

Specific wartime service,

-

Specific communities and villages,

-

Hereditary posterity “by either sex,”

-

And individual ascertainment through sworn proof.

They do not create collective corporate owners. They do not vest rights in councils. They vest obligations in the Crown toward identifiable persons and their descendants.

8. Individual Lineage, Not Abstract Collectives

The language of the Proclamation—“the Mohawk Nation and such others”—did not create a corporate body. Courts have repeatedly acknowledged this. Nor did the Haldimand Pledge promise restoration to an undifferentiated confederacy. It referred to specific Mohawk villages whose steady attachment justified the Crown’s commitment.

Later substitution of administrative bodies for hereditary beneficiaries has no foundation in the original instruments.

9. Continuity Into the Modern Period

In 1914, Canada created the United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada, now the country’s only federally incorporated genealogical body dedicated to identifying Loyalist descendants. While not identical to Simcoe’s magistrate process, it reflects the same constitutional idea: Loyalist posterity must be proven, not presumed.

Recognition through UELAC can extend upward to the Canadian Heraldic Authority, allowing verified descendants to bear the Loyalist Coronet in registered arms. This confirms that the U.E. remains a living hereditary dignity tied to individuals, not collectives.

10. Why Logan v. Styres Still Matters

Logan v. Styres is often cited to deny standing to hereditary or traditional claimants. Properly understood, it demonstrates something narrower and more troubling: standing was rejected without applying the Crown’s own method for identifying who stood.

Neither the pledge of restoration, nor the problem identified in Jackson v. Wilkes, nor the solution supplied by Dorchester and Simcoe was addressed.

This is not extinguishment. It is unfinished constitutional work.

Leave a Reply