-

Case Title & Citation

Moore v. Sweet, 2018 SCC 52, [2018] 3 S.C.R. 303. -

Decision Summary (Neutral Overview)

This case involved competing claims to the proceeds of a life insurance policy.

-

The deceased originally named his then-wife, Michelle Moore, as irrevocable beneficiary of his life insurance policy.

-

After they separated, he made a private agreement with her: she would continue to pay the premiums and, in return, remain the beneficiary.

-

Later, he changed the named beneficiary on the policy to his new common-law partner, Rhesa Sweet, without telling Moore and without Moore’s consent.

-

When he died, the insurer was contractually bound to pay the proceeds to Sweet as the named beneficiary.

The Supreme Court of Canada held:

-

As between the two claimants, it would be unjust for Sweet to retain the money because Moore had paid all the premiums after separation, relying on their agreement.

-

A constructive trust in favour of Moore should be imposed over the policy proceeds, even though the insurance contract itself pointed to Sweet.

Moore won; the policy proceeds were awarded to her.

-

Historical & Legal Context

Moore v. Sweet is a leading modern case on unjust enrichment and constructive trust in Canada. It clarifies:

-

How unjust enrichment can apply even where a valid contract exists in the background (here, the insurance contract).

-

When a proprietary remedy (constructive trust) is appropriate, rather than just money damages.

It is widely cited for the three-part test for unjust enrichment (enrichment, corresponding deprivation, absence of juristic reason) and for its treatment of “juristic reasons” such as contracts and statutes.

-

Key Legal Principles Identified in the Case

-

Unjust Enrichment Test

-

The defendant has been enriched.

-

The plaintiff has suffered a corresponding deprivation.

-

There is no juristic reason (recognized legal basis) for the enrichment.

-

-

Juristic Reason Analysis

-

First step: look at established categories (contract, gift, disposition of law, etc.).

-

Second step: if no established reason applies, consider the parties’ reasonable expectations and public policy.

-

-

Constructive Trust as Remedy

-

A constructive trust may be ordered when:

-

A monetary award is inadequate, and

-

There is a sufficient link between the plaintiff’s contribution and the disputed property.

-

-

-

Statutory and contractual mechanisms (like beneficiary designations) do not always block equitable relief where those mechanisms are used in a way that is equitably wrong.

-

Implications for Haldimand, Loyalist, and Mohawk Questions

Moore v. Sweet matters to Six Miles Deep in several ways:

-

It shows that courts are willing to look past the surface of a formal instrument (here, the insurance contract naming Sweet) and ask:

-

Who actually paid?

-

Who relied?

-

Who is being unjustly enriched?

-

-

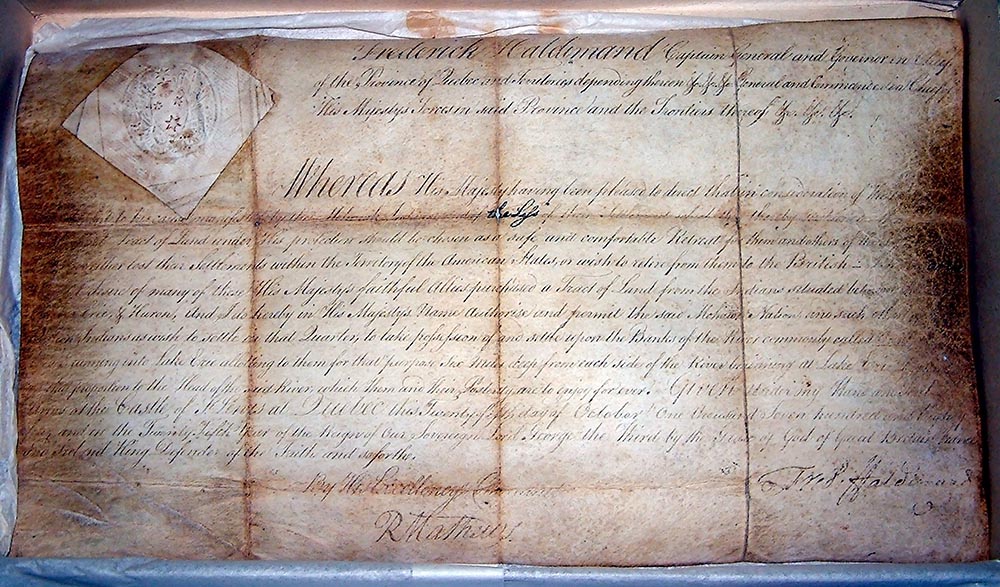

Applied to Haldimand lands, this logic supports arguments that:

-

Canada, Ontario, municipalities, and private owners have been enriched for generations (taxes, rent, development profits).

-

Mohawk Loyalist posterity has suffered a corresponding deprivation (loss of use, jurisdiction, revenue, security).

-

There is no valid juristic reason that can override the explicit Haldimand grant “for them and their posterity forever,” and the later 1791 confirmation.

-

-

Just as the named beneficiary in Moore could not keep the windfall once the court understood the underlying arrangement, modern title-holders and governments on Haldimand lands may have to face that their apparent “beneficiary” status is vulnerable to equitable correction.

-

Points of Interest to Mohawk of Grand River Posterity

-

Moore v. Sweet gives a clear template for unjust enrichment on Haldimand lands:

-

Enrichment: decades of taxation, development gains, and governmental revenue based on treating the tract as ordinary provincial land.

-

Deprivation: Mohawk and Loyalist posterity being displaced from their refuge, denied jurisdiction, and cut off from the benefits promised to them.

-

No juristic reason: the Haldimand Proclamation and its confirmation stand in direct conflict with the idea that Canada/Ontario can take those benefits as if they were free.

-

-

It also supports the idea of constructive trust over land and revenue:

-

Courts can, in principle, recognize that even if someone holds legal title or collects taxes, they may be holding in trust for another party who was supposed to be the true beneficiary (here, Mohawk Loyalist posterity).

-

-

The case helps translate your language about “trust de son tort,” Crown misadministration, and unjust taxation into a doctrinally familiar remedial framework for judges.

-

Unresolved Questions / Future Research Directions

-

How would a court define the property for a constructive trust in the Haldimand context?

-

Specific parcels of land?

-

A stream of tax revenue from the tract?

-

Proceeds from particular developments (e.g., large commercial projects)?

-

-

Could the court impose systemic constructive trusts, or would it proceed claim-by-claim (specific parcels, specific projects)?

-

How would the “juristic reason” analysis handle:

-

The 1791 confirmation of Haldimand,

-

Later statutes (e.g., Indian Act, municipal acts), and

-

The doctrine that constitutional instruments cannot be quietly overridden?

-

-

Sources

-

Moore v. Sweet, 2018 SCC 52, [2018] 3 S.C.R. 303.

-

Canadian law commentary on unjust enrichment and constructive trust remedies.

Leave a Reply