|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

In this series, we have examined the Grand River not as a single dispute, but as a sequence of decisions that were never meant to be understood in isolation. From the wartime losses acknowledged by the Crown in 1779, to the land set apart along the Grand River in 1784, to the hereditary recognition and oath-based processes that followed, a consistent settlement logic begins to surface. What the historical record reveals is not confusion about what was promised, but a slow unraveling of how that promise was supposed to be maintained—and how its quiet abandonment came to shape everything that followed on the Grand River.

The sequence begins in 1779 with the Haldimand Pledge. Governor Frederick Haldimand acknowledged that specific Mohawk villages—Canojaharie, Ticonderoga, and Aughugo—had been ruined because of their steady attachment to the King’s cause during the American Revolution. These were not incidental losses. They were sacrifices made in service to the Crown. Haldimand ratified Sir Guy Carleton’s promise that, once the war ended, those Mohawks would be restored to the same condition they had enjoyed before hostilities broke out. In modern terms, this was a commitment to status quo ante bellum: full restoration, not mitigation.

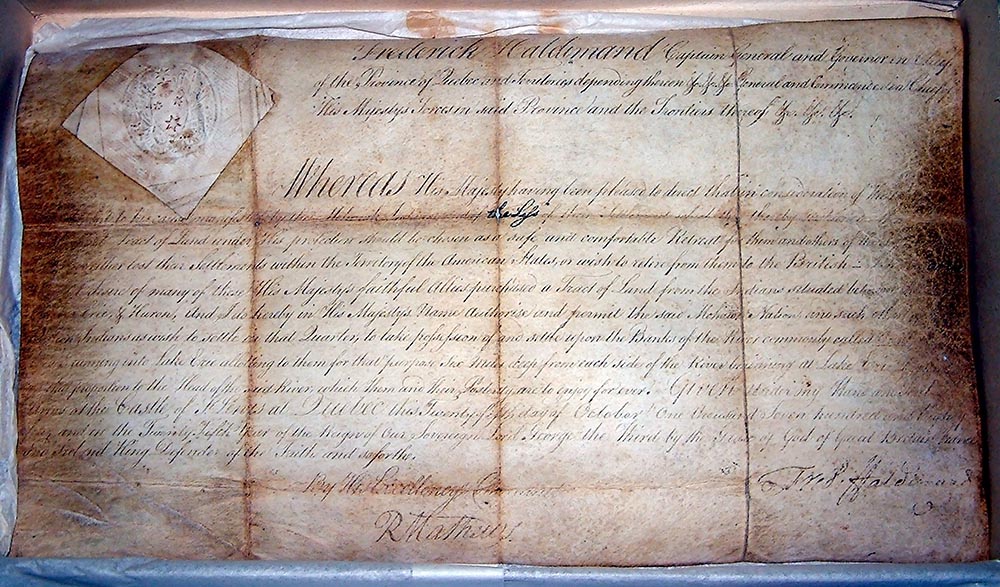

That pledge was given territorial form in 1784. The Haldimand Proclamation authorized the Mohawk Nation, and such others of the Six Nations as wished to retire with them, to take possession of lands along the Grand River, six miles deep on each side, to be enjoyed by them and their posterity forever. The wording matters. The land was purchased by the Crown, set apart under royal protection, and granted perpetually. This was not an ordinary Indigenous occupancy arrangement. It was a Loyalist settlement grounded in alliance, service, and Crown honour.

Yet embedded in the proclamation was a structural weakness that later courts would exploit. The instrument did not name any individual grantee in a natural capacity. It referred to the “Mohawk Nation and such others,” without creating a corporation, a body politic, or identifying living persons through whom the interest could pass. Nineteenth-century courts treated this absence as fatal. Without named natural persons, the interest was assumed to be incapable of succession in ordinary property-law terms and therefore vulnerable to collapse once the original generation passed.

This was not a problem the Crown failed to notice. It was a problem the Crown actively moved to repair.

In 1789, Lord Dorchester issued what he called a Mark of Honour for those families who had adhered to the unity of the Empire and joined the Royal Standard before 1783. His instruction was explicit: Loyalist families and their descendants, by either sex, were to be distinguished in parish registers, militia rolls, and public records so their posterity could be identified and preferred for future benefits and privileges. This was not symbolism. It was legal infrastructure. The Mark of Honour supplied what the Haldimand Proclamation lacked—an identifiable hereditary line anchored in natural persons.

John Graves Simcoe completed the mechanism in 1796. Recognizing that Dorchester’s registry had not been consistently implemented, Simcoe ordered Loyalist claimants to ascertain their status upon oath before magistrates. Those who did so would be confirmed in their lands without fee. Those who failed to come forward would not be entitled to that benefit. This was not punishment. It was procedure. The Crown provided a clear path to convert honour into legally recorded standing.

Taken together, these instruments formed a coherent system. The pledge acknowledged the debt. The proclamation supplied the land. The Mark of Honour identified the hereditary beneficiaries. The oath-based ascertainment process converted lineage into legally cognizable standing. Nothing essential was missing—except continuity.

Canada did not maintain the registries. The ascertainment process fell into disuse. The hereditary framework was allowed to atrophy. When courts later encountered disputes on the Grand River, they saw an incomplete record and treated the absence as evidence of extinction rather than administrative neglect. The failure of Crown machinery was mistaken for the failure of Crown obligation.

This misreading had lasting doctrinal consequences. Courts increasingly characterized the Haldimand grant as a form of Aboriginal usufruct rather than Loyalist compensation. Once that framing took hold, the Crown was treated as retaining underlying title and therefore free to dispose of the land. The grant was no longer read as a perpetual hereditary settlement, but as a generalized Indigenous interest subject to Crown administration.

That interpretation does not sit comfortably with the language or structure of the original bargain.

The grant was not framed as a temporary right contingent on constant assertion. It was granted “to them and their posterity forever.” That language does not describe an interest that diminishes over time. It describes a hereditary dedication whose beneficiaries expand rather than disappear. The land was not given to Joseph Brant personally, nor exhausted by his actions. It was oriented forward, toward posterity.

This distinction also clarifies why not all Indigenous litigants stand in the same relationship to the Haldimand Proclamation. In recent decades, litigation concerning the Grand River has sometimes been advanced by individuals or groups explicitly stating that they do not act on behalf of Indian Act band councils. That distinction is important—but it does not automatically confer standing under the Haldimand framework.

The interests created by the Haldimand Pledge, Proclamation, Mark of Honour, and Simcoe’s ascertainment process are sui generis. They are Loyalist-hereditary interests tied to specific service, specific posterity, and a specific Crown mechanism for identification. Those who descend from other Indigenous nations, or who assert rights grounded in broader Aboriginal law, may well have legitimate claims of their own. But that does not make them beneficiaries of this particular instrument.

This is not a criticism of those claims. It is a jurisdictional fact. The Haldimand Proclamation does not create a general Indigenous entitlement. It creates a defined Loyalist settlement whose beneficiaries were meant to be identified through lineage and public record. Standing under that framework cannot be assumed, borrowed, or collectivized. It must be proven in the manner the Crown itself prescribed.

Canada once understood this distinction. In the early twentieth century, ministers acknowledged in Parliament that Mohawks occupied a different legal footing than other populations. In 1919, Canada sought clarification from the British Parliament as to whether the Haldimand Proclamation had ever been denounced and whether Six Nations were subject to Canadian legislation. The answer was clear: the proclamation had not been revoked and was treated as a special treaty-like instrument.

The response was not restoration, but avoidance. In 1924, the Canadian government forcibly removed the traditional council at Grand River, seized constitutional wampum records, and imposed Indian Act governance. The act was administrative in form but constitutional in effect. It displaced the very structures through which hereditary standing and Crown relationships had been expressed.

Ironically, Canada preserved Loyalist heredity elsewhere. In 1914, it incorporated the United Empire Loyalist Association of Canada to ascertain Loyalist descent nationwide. Through it, individuals can obtain certificates of descendantsand carry that recognition into the highest reaches of the Crown, including heraldic acknowledgment under the Governor General’s authority. The Crown has always known how to recognize hereditary Loyalist standing. It simply refused to apply that knowledge where it mattered most.

None of this requires new legislation. The Grand River settlement predates Confederation and was explicitly confirmed as part of Canada’s constitutional order in 1791. The duty is not to innovate, but to observe. Failure to observe a legal duty is not merely a civil oversight. It is a constitutional breach.

The remedy, therefore, is not negotiation but completion: rebuilding the hereditary registry, reinstating ascertainment mechanisms, distinguishing Loyalist posterity from statutory collectives, and restoring exclusive use and enjoyment where it was never lawfully surrendered.

Canada’s legitimacy on the Grand River does not rest on convenience or consensus. It rests on whether the Crown is prepared to finish what it began—to perform, at last, the promise it made to posterity.

The promise was made.

The framework was built.

The failure was not legal.

It was administrative—and it remains unfinished.

Leave a Reply