|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

When a newcomer becomes a Canadian citizen, they stand in a room, raise their right hand, and swear an oath to the King. When a councillor, police officer, judge, or MP takes office, they do the same. It feels like ceremony: a few words, a handshake, a photo.

Buried inside that oath is a question almost nobody wants to touch: what happens when the constitutional promises you swear to uphold contradict the way Canada actually behaves on the ground?

On the Haldimand Tract along the Grand River, that contradiction is not abstract. It is written down, signed and sealed, and still hanging over every acre.

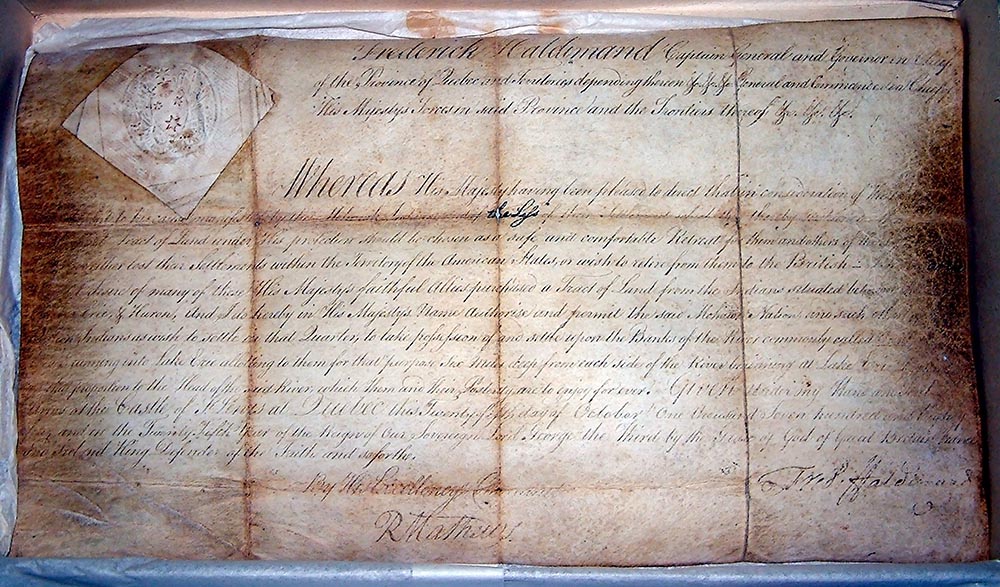

In 1784, Governor Frederick Haldimand set apart a “safe and comfortable retreat” along the Grand River, six miles deep on each side, for the Mohawk Nation and their posterity “to enjoy forever.” Five years later, Lord Dorchester added a Mark of Honour for families who had adhered to the unity of the Empire and joined the Royal Standard before 1783, creating the United Empire Loyalist (U.E.) designation and ordering that these descendants “by either sex” be distinguished in public records for future benefits and privileges. Simcoe then tried to build the next step: a process where Loyalists would “ascertain upon oath” who they were in open court, so their lands could be confirmed by deed without fees.

These instruments were how the Crown purchased peace, secured alliances, and stabilized this region after the American Revolution. And in 1791, when the new constitutional framework for what became Upper Canada was set up, the Haldimand arrangement was confirmed “to uphold the honour of the Crown.” Once that happens, Haldimand is not a souvenir. It becomes part of the constitutional architecture Canada inherits.

On paper, the Crown knew exactly who it was talking to: Mohawk allies and Loyalist posterity on a defined corridor, enjoying that land under royal protection “forever.”

Two centuries later, the daily reality on Six Miles Deep looks nothing like that promise. Municipalities tax the land as if it were ordinary Ontario real estate. Provincial and federal laws are enforced without a second thought. Band councils, created under the Indian Act, are treated as universal representatives, even though the original grants and pledges speak to a narrower Mohawk Loyalist posterity and to specific nations. Developers cut up lots; banks mortgage them; police patrol subdivisions that sit right inside what was supposed to be a protected corridor.

Everyone behaves as if Canada’s claim to full sovereignty here is beyond question. But the oath of allegiance that newcomers and officials swear points in a different direction. It ties them, not to whatever is convenient today, but to the constitutional order that already exists.

In McAteer v. Canada (Attorney General), people like Dror Bar-Natan challenged the citizenship oath. They argued that swearing allegiance to the Queen violated their political convictions. The Ontario Court of Appeal rejected the challenge, but in doing so it explained what the oath really means. The court said the oath is not about personal loyalty to a human monarch. It is an expression of agreement with “the fundamental structure of our country as it is,” and allegiance to the Queen is allegiance to a symbol of the state and its constitutional order, not to an individual personality.

Taken seriously, that logic cuts both ways.

In the same decision, the Court made another crucial point: the Charter cannot be used to attack another part of the Constitution. You can’t use a Charter challenge to erase the Crown itself, because the monarchy is part of the constitutional framework that gives the Charter its force. The Constitution has to be read as a whole. That logic matters for Haldimand too. If the oath ties people into the constitutional structure “as it is,” then you can’t selectively pretend that the parts you don’t like—such as the Haldimand Proclamation and its 1791 confirmation—have somehow fallen out of that structure while the rest remains intact.

If the oath is consent to the structure of Canadian society, and that structure includes the Haldimand Proclamation and its confirmation to uphold Crown honour, then everyone who swears the oath has stepped into a constitutional duty imposed by law. They inherit the Crown’s old obligations as part of the deal. The same is true for an oath of office. When a councillor, judge, or police officer signs that document, they are not just promising to enforce whatever statutes are on their desk; they are promising to operate inside the constitutional limits that already include a Mohawk refuge on the Grand River.

That is why the usual excuses—“we weren’t taught that,” “it’s not written on the oath card,” “it’s above my pay grade”—don’t really hold. Ignorance may explain how we got here. It doesn’t erase the duty once people are put on notice.

This becomes even sharper when you look at citizenship and place of birth.

Canada likes to frame citizenship through jus soli—if you are born on Canadian soil, you are Canadian. But what exactly counts as “Canadian soil” on land that was purchased and granted as a Mohawk refuge, promised for the “exclusive use and enjoyment” of Mohawk posterity and those who retire to their quarter, and then constitutionally confirmed?

There is a modern example of how seriously the Crown can treat this question when it wants to. In 1943, during the Second World War, Princess Juliana of the Netherlands gave birth to Princess Margriet at the Ottawa Civic Hospital. To protect Margriet’s place in the Dutch line of succession and avoid making her a British subject by jus soli, the Canadian government used a wartime legislative measure to create a temporary extraterritorial bubble around the maternity suite. For the moment of birth, that space was treated as outside Canadian territory so that Dutch law—jus sanguinis, citizenship by blood—could operate cleanly.

The point is not to copy that model for Mohawk people. If Haldimand and the 1791 confirmation sit at the constitutional level, then Mohawk refugees and their posterity do not need a special one-off statute to make their land “not Canada.” The refuge status is already part of the Crown’s own structure. The Princess Margriet story simply shows how far the Crown is willing to bend domestic law when it cares about honour, succession, and the continuity of its promises.

On the Grand River, the Crown has shown no such urgency. Children are born in hospitals and homes on Haldimand lands every day. Their birth certificates treat the territory as ordinary provincial ground. Their citizenship papers never mention that, by the Crown’s own instruments, they were born inside a corridor that was supposed to remain in Mohawk hands forever. At minimum, it means their citizenship sits on top of unresolved Mohawk title and jurisdiction, not cleanly apart from it.

Real estate law tries to soften that problem with the idea of the “innocent third-party purchaser”—a buyer who relies in good faith on the land registry and doesn’t know about any deep defects in title. In that frame, homeowners are blameless; the problem lies somewhere in the distant past.

But along Six Miles Deep, that innocence has a limit. Once you accept that Haldimand is part of Canada’s constitutional story, and once people have been told it exists and was confirmed to uphold Crown honour, it becomes harder to say “we had no reason to suspect anything.” Newcomers who take the oath, councillors who sign oaths of office, developers who work hand-in-glove with municipalities and the Grand River Notification Agreement—all of them are now operating with implied consent to a structure that includes Mohawk refuge rights, not just the provincial statute book.

That is one reason some of us talk about purchasers and officials as “innocent but not blameless.” The deeper design is not their fault; they didn’t draft the Indian Act or redraw county lines. But they are participating in a system that rests on a constitutional breach of a specific promise: that this corridor was to be a safe and comfortable retreat for Mohawk families and their posterity, “forever.”

The Supreme Court of Canada has already faced situations where an entire body of laws turned out to be unconstitutional. In the Manitoba language rights reference, the Court declared Manitoba’s unilingual English laws invalid because the constitution required laws to be enacted in both English and French. The justices recognized that striking everything down at once would create chaos, so they gave the province a window to re-enact its laws properly. But they did not pretend the breach wasn’t real. They acknowledged it and required a cure.

That case is a warning and an opportunity. It shows that courts can look at generations of practice, admit that it was built on a constitutional error, and still choose an orderly path back to legality. Applied to Haldimand, that would mean recognizing that provincial, federal, and municipal legislation has been applied on lands where the Crown had already pledged exclusive use and enjoyment to Mohawk posterity. It would mean treating that misapplication as a constitutional breach, not a minor historic wrinkle.

From Canada’s side, that is not just a legal headache. It is a national security problem in the constitutional sense. If millions of people discover that the land they live on was supposed to be part of a Mohawk refuge; that taxation, policing, and development there may have been ultra vires; and that citizenship status is layered over unresolved title, it will shake confidence in the story Canada tells about itself. The temptation will be to double down on silence and treat Haldimand as too dangerous to discuss.

From the Mohawk side, it is a different kind of security question. Haldimand was meant to be a shield—a refuge after villages in New York were burned for staying loyal to the Crown. When that shield is treated as interchangeable real estate, the survival project it was meant to secure is undermined. Land is not just an asset on a tax roll; it is the condition for language, clan law, and political continuity.

So where does that leave us?

It leaves us in a place where oaths have to mean something again. If the Oath of Allegiance is consent to the actual structure of Canadian society, then that structure must be told truthfully—including Haldimand, Dorchester, and Simcoe. If an oath of office binds ministers, councillors, officers, and judges to uphold the constitution, then they cannot selectively ignore the parts that are inconvenient on the Grand River.

It also leaves us with tools: writs of mandamus to force public bodies to discharge their constitutional duties; declaratory relief to state clearly where legislation is invalid on Haldimand lands; forensic accounting of unjust enrichment; and, if necessary, international arbitration in fora that understand treaties, pledges, and quasi-international instruments.

Most of all, it leaves us with a simple, stubborn fact: the Crown wrote these promises down. It confirmed them to uphold its own honour. People today swear oaths into that same Crown every single day.

The question now is whether those oaths will finally be read all the way through—backwards into 1779, 1784, 1789, 1791, and forwards into the lives of the Mohawk posterity who still live on Six Miles Deep.

Terms used in this entry

- Lexicon: Haldimand Tract

- Lexicon: Safe and Comfortable Retreat

- Lexicon: Six Miles Deep (Concept)

- Lexicon: Mark of Honour

- Lexicon: By Either Sex (U.E. Rule)

- Lexicon: Ascertain Upon Oath

- Lexicon: Honour of the Crown

- Lexicon: Indian Act

- Lexicon: Mohawk Loyalist Posterity

- Lexicon: Oath of Allegiance (Haldimand Context)

- Encyclopedia: Haldimand Proclamation of 1784

- Lexicon: Exclusive Use and Enjoyment

- Lexicon: Innocent Third-Party Purchaser / Good-Faith Purchaser

- Lexicon: Ultra Vires (Beyond Powers)

- Lexicon: Writ of Mandamus

- Lexicon: Declaratory Relief

Where these terms are used in posts and pages

- Haldimand Tract: WAKONRORI — “I TOLD YOU SO”: Bridges, Boldness, and the Unfinished Question Beneath the Grand River

- Safe and Comfortable Retreat: Timeline

- Mark of Honour: HONOUR WITHOUT END: How the Crown Rewarded Mohawk Loyalists—and How that Promise still Binds Canada

- By Either Sex (U.E. Rule): Lineage Map

- Ascertain Upon Oath: Mark of Honour

- Honour of the Crown: ACQUISITION FIRST, DEDICATION CONFIRMED: The True Legal Story of an Acquired Territory

- Indian Act: WAKING THE SLEEPING NATIONS: Allegiance, Surveillance, and the Architecture of Sovereignty

- Mohawk Loyalist Posterity: WAKING THE SLEEPING NATIONS: Allegiance, Surveillance, and the Architecture of Sovereignty

- Haldimand Proclamation of 1784: BEFORE THE WRITS: Building a Public Record for Mandamus and Quo Warranto on the Haldimand Proclamation

- Exclusive Use and Enjoyment: WAKING THE SLEEPING NATIONS: Allegiance, Surveillance, and the Architecture of Sovereignty

- Writ of Mandamus: Writ of Mandamus

- Declaratory Relief: Declaratory Relief

Leave a Reply