The honour of the Crown is a constitutional principle that says the Crown must act with integrity, fairness, and good faith in all dealings with Indigenous peoples. It is more than a moral slogan; it is a legal standard courts use when interpreting treaties, proclamations, and historic promises. When the Crown gives its word—especially in writing, in council, and before witnesses—that promise is supposed to bind not just the officials of the day, but the Crown in every generation.

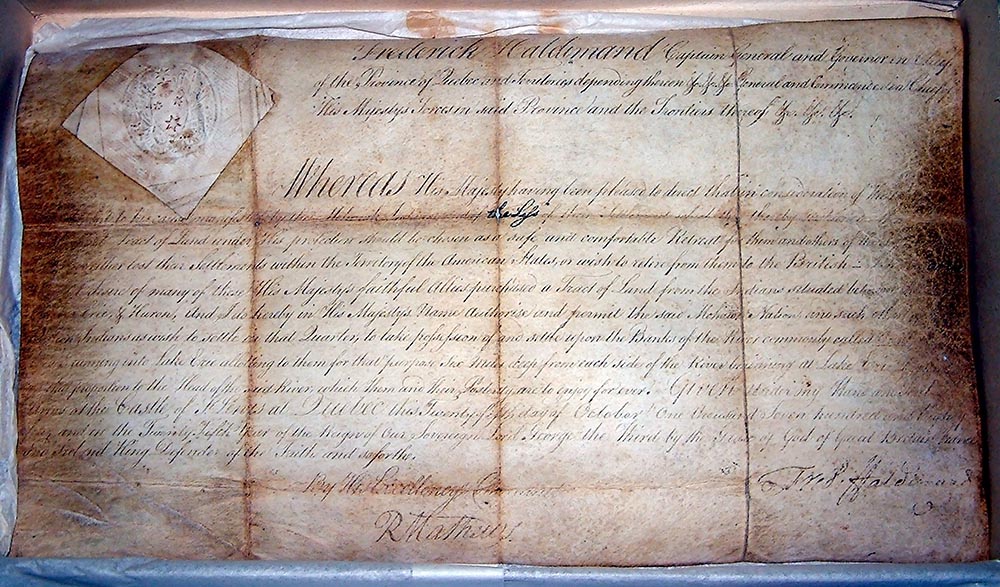

In the Haldimand story, the honour of the Crown is not an abstract idea; it was explicitly acknowledged by Crown officials themselves. In committee, after reviewing Mr. Jones’s survey of the Grand River lands promised to the Mohawk Nation and the tract at the Bay of Quinte, the members stated that “the faith of Government is pledged” to the Mohawk chiefs for those two tracts. Because that faith was pledged, they said, every precaution ought to be taken to preserve the Mohawks in the quiet possession and property of those lands.

The committee did not stop there. They recommended that either (1) an Act of the provincial legislature, or (2) a grant under the Great Seal of the Province be issued in favour of the principal chiefs, on behalf of their nation, or to persons in trust for them for ever. In other words, they recognized that honour was not just a feeling; it required concrete legal instruments—statutes or Great Seal grants—to secure what had been promised and to protect the Mohawk interest in law.

Read alongside the Haldimand Proclamation, that committee passage is a smoking gun for honour of the Crown in practice. It shows that:

-

Officials understood the Mohawk grants as a matter of pledged faith, not mere policy generosity.

-

They saw a duty to protect Mohawk possession, not to whittle it away.

-

They proposed using the strongest provincial tools available—legislation or Great Seal grants—to carry that duty into effect “for ever.”

In the Six Miles Deep framework, this becomes a measuring stick for our time. If honour once meant securing Mohawk lands by formal legal instruments and guarding quiet possession, then the modern Crown cannot claim to be honourable while allowing those same lands to be taxed, subdivided, mortgaged, and developed as ordinary provincial real estate, without completing the protective steps its own officials recommended.

Honour of the Crown, in this sense, means three things on the Grand River:

-

Owning the pledge – openly acknowledging that the “faith of Government” was pledged to Mohawk chiefs for specific tracts, including the Grand River, and that this pledge still rests on the modern Crown.

-

Finishing the work – using today’s legal tools (registries, declaratory judgments, statutes, modern “Great Seal” instruments) to do what the committee recommended: clearly secure and protect the Mohawk interest in those lands on behalf of the nation and its posterity.

-

Aligning practice with promise – ensuring that land use, taxation, policing, and development follow from that pledged faith, instead of pretending the pledge never happened.

When Haldimand, Dorchester, Simcoe, and the committee speak of pledges, posterity, “for ever,” and the need to preserve Mohawk possession, they are giving us the Crown’s own description of what honour requires. The honour of the Crown today is judged by whether those same commitments are finally carried through—not only in words, but in the legal and political structures that govern Six Miles Deep.

- https://electriccanadian.com/makers/carchives1896.pdf