The Mark of Honour is Lord Dorchester’s term for the special hereditary recognition he proposed in 1789 for families who “adhered to the unity of the Empire and joined the Royal Standard” before the Treaty of Separation in 1783. In his Council minute, Dorchester directed that these Loyalists and their descendants should be distinguished in parish registers, militia rolls, and other “public remembrancers” of the Province, and treated as “proper objects” for “distinguished benefits and privileges.” Attached to this was a note explaining that such Loyalists, “and all their children and their descendants by either sex,” were to be marked with the capitals U.E. after their names—“alluding to their great principle, the unity of the Empire.”

This is not a casual label. The Mark of Honour is a Crown-created hereditary dignity. Unlike most honours, which die with the original recipient, Dorchester’s scheme is explicitly built for posterity. The U.E. mark is meant to follow the bloodline down through generations, through mothers or fathers (“by either sex”), and to appear not just in family stories but in the official record-keeping of the state: church books, militia lists, and any other public registers that track who people are. In other words, the Crown intended to build a long-term registry of Loyalist posterity into the everyday paperwork of the colony.

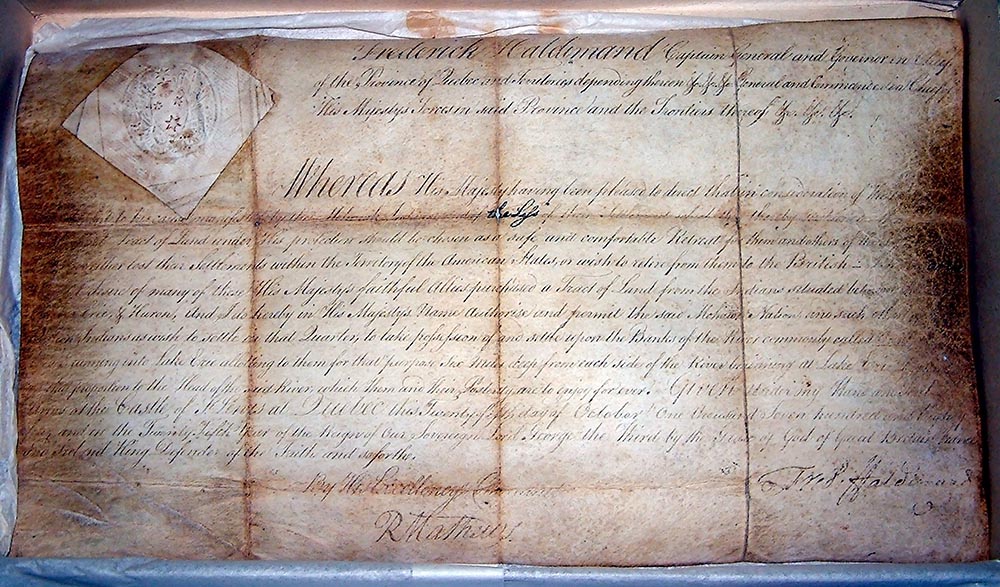

In the Six Miles Deep framework, this Mark of Honour sits directly on top of Mohawk and Grand River history. Many Mohawk families on the Haldimand Tract are both Haudenosaunee by clan law and U.E. by Loyalist descent. That overlap matters. It means the Crown didn’t just grant land in 1784 and walk away; within a few years it had also created a hereditary category—U.E. posterity—that was supposed to be tracked and favoured over time. When you put Dorchester’s Mark of Honour together with the Haldimand Proclamation (“them and their posterity… forever”) and the Simcoe Proclamation (“ascertain upon oath” in court and confirm deeds without fee), you can see a deliberate framework emerge:

-

Haldimand provides the territorial refuge on the Grand River.

-

Dorchester creates a hereditary class of Loyalist posterity, to be visibly marked and recorded.

-

Simcoe sets out a procedural bridge, requiring Loyalists to prove their status on oath so it can be confirmed in law.

Viewed this way, the Mark of Honour is evidence that the Crown never meant Loyalist Mohawk posterity to disappear into generic “settler” or “band member” categories. It meant to keep those families visible and distinguishable in law for future benefits and protections. The fact that registries were incomplete, and that later governments treated U.E. as mere genealogical trivia, does not erase the original design. It highlights the Crown’s responsibility for abandoning its own hereditary framework—and strengthens the case for rebuilding a modern registry and remedy structure that finally takes the Mark of Honour seriously on Six Miles Deep.

In the generations since Dorchester, Canada has moved in the opposite direction. Parliament and policy-makers have effectively shut the door on creating or recognizing new hereditary titles and aristocratic honours. In practical terms, that leaves only two living hereditary Crown dignities in the Canadian constitutional space:

- the King/Queen (the hereditary sovereign who holds the Crown in right of Canada), and,

- the United Empire Loyalist (U.E.) Mark of Honour, carried by descendants “by either sex.”

That makes the U.E. designation extraordinarily rare. It is not an Aboriginal hereditary title and it does not come from the Indian Act or band lists; it is a Crown-created, imperial-era dignity that still runs down specific bloodlines.

On Six Miles Deep, this matters because it shows that Mohawk Loyalist posterity on the Grand River are standing at the junction of the only two hereditary Crown lines Canada still carries: the royal house itself, and the U.E. mark Dorchester ordered. In a legal system that now refuses to create new hereditary titles, the continued existence of this old one is a standing reminder that certain families and certain promises were always meant to endure—and that the Crown still has unfinished business with the posterity it chose to mark.